Celebrating Piri Thomas and the Permission He Gave Us

In the New York metropolitan area, it was a day to remember the dead. In Newark, r&b royalty (and Kevin Costner) mourned the loss of Whitney Houston. In the Bronx, the Afro-Caribbean community (with the help of Reverend Al Sharpton) writhed in sadness over the death of Ramarley Graham, an 18-year-old who was shot to death in the bathroom of his family home because the police thought he was armed.

They thought he was armed.

And in El Museo del Barrio in Harlem the diaspo-Rican and greater familia got together to pay tribute to Piri Thomas, who died under less dramatic circumstances last October and left a legacy that formed the basis for the identity of a community. Thomas would have understood the pain felt by the Graham family–he said as much in this interview with Carmen Dolores Hernández in 1995:

The violence, the sirens, the police cars and the stories that you heard and the brutalities that you saw led you to arrive at the conclusion that we didn’t need police protection, what we did need was protection from the police.

But this was not a night for wails, tears or anger. It was a night, where the imaginary Boricua/Latino nation remembered its black prince. Fellow poets like Martin Espada, Papoleto Meléndez, Nancy Mercado, Willie Perdomo, Mayda del Valle, Junot Díaz, Emmanuel Xavier, Lemon Anderson, y Rich Villar reflected on their memories, sharing the stage with community leaders Felipe Luciano and Marta Moreno Vega and publishing activist Marcela Landres. And before and after the show there was sharing too, among the audience and the participants, creating an energy that moved Luciano to marvel about seeing people that he hadn’t seen for years.

Everyone seemed to agree that although Piri had every right to have become consumed by bitterness, he chose to embrace love.

photo credits et al: Champion Hamilton

Thomas played “the unseen music,” said Espada, invoking Piri’s spirit through the words of the poet Lucille Clifton: “Come celebrate with me that every day something has tried to kill me and failed.” His tribute culminated with his poem “Imagine the Angels of Bread,” which dreamed the world in reverse, a parallel planet where the poor wind up winning.

A recurrring theme of the evening was how the writer expressed gratitude to Piri for giving them “permission” to tell their stories. Before the publication of “Down These Mean Streets,” the short-story collection that gave Thomas his immortality, most of his audience had no voice. The noisy, unfiltered and bittersweet stories that Piri told announced the dawn of the Nuyorican century (we’re only halfway through it!) It can be read as a tropicalization of the streets or simply a new American other-narrative, or a profane yet sacred dance between the two.

But as Luciano reminded us, in his newfound persona as Reverend of the Church of the Corazón del Barrio, the central revelation of Piri’s work was his confrontation with the severe politics of binary racial categories that are imposed in the United States, and how that experience revealed the hidden racism of his ancestral homeland. “That’s me–a skinny dark-skinned, curly haired Puerto Rican,” murmured Papoleto Meléndez, gazing at the projected fotos of Piri with Pedro Pietri,with Miguel Algarín, with Willie Bob’s bugaloo “Fried Neckbones and Home Fries” playing softly in the background.

“He knew the pain of color,” insisted Luciano. “He talked about being black, and how we still can’t admit that we have an African past. The moment that we admit that is when we start becoming healthy again.”

The panel moderated by Moreno Vega brought up anger as a positive energy, spoke about the laws drafted in Arizona to take books by writers like Piri out of the libraries, about emergent fascism. The participants also hammered home the prison-industiral complex that has incarcerated a huge chunk of an entire generation, as well as the famous “stop and frisk” policy that makes criminals out of the innocent. Things that Piri always talked about.

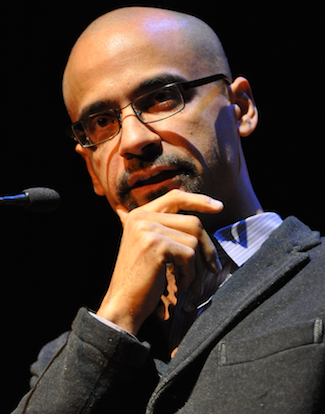

In the evening’s third act, Junot Díaz reminded us that the spirit of Piri was inclusive of diversity, which is another essential aspect of the Boricua-Latino identity. Like the extended family of repeating islands, Thomas also had roots in Cuba, and because of that our nation is not limited to Puerto-Rockeños. In that way Díaz, tripping the light sarcastic, with a droll dose of vulgarity and hilarity, manifested the 100% of Big Pun and beyond. His landmark collection “Drown” can be read as a suburban version of “Down These Mean Streets,” y Díaz was relentless in giving Piri the credit for creating a space for his alternative quisqueya universe.

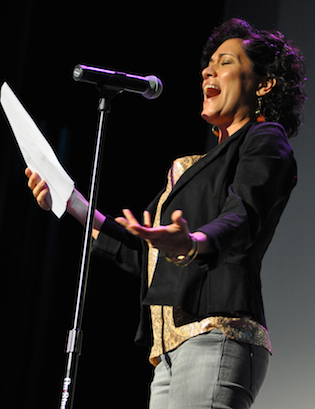

Mayda del Valle shined like the “slam poetry” queen that she is, with her poem about the search of spiritual identity and another theme of the evening: coming to terms with the loss of a loved one. For her, it was an encounter with African tradition that looked to dialog with the ancestors to see what could be done in the future. Piri had granted her permission to investigate how the spirits translate themselves into everything in history that has been lost.

Willie Perdomo, the true inheritor of the Piri Thomas tradition, told us in simple and direct terms the literary brotherhood that arose from sharing words and ideas. He spoke of Thomas’s tendency to read the work of friends in public, like one night in the ’90s where at a reading at Hunter College, he read poems by Willie and Pedro Pietri. “That night Piri read ‘ThePuerto Rican Obituary’ and ‘Nigger-Reecan Blues,’ and I knew that I was ready to put that poem to rest,” remembered Perdomo. It was the poem that put Perdomo on the map, another reflection on the muddy waters of Afro-Latino identity, about the beautiful broken-down streets, and now it was time to find a new way to grow.

“I asked myself, ‘Is there a way to become a man without going through hell?'”

Everyone that carries El Barrio in their heart knows the answer. For his last poem, Perdomo chose one dedicated to his son–“To read is to be free,” he intoned, and while he pronounced these words a small child began to cry. They were tears of joy.

All that was left was for Gary Santana, the organizer of the event to introduce Piri’s widow, Suzie Dod Thomas, who had met him in 1986 in the process of translating Down These Mean Streets. She assured us that there was no doubt that Piri’s spirit was, in one way or another, presente, and ended the tribute with the word that he liked to use in moments like these:

“Punto.”

Archived from May 2011:

The amazing thing about “Día,” a photographic exhibition recently shown in the arty Brooklyn neighborhood known as DUMBO, is how it records the birth of the Nuyorican. Yet the photographers–Frank Espada, Ricky Flores, David Gonzalez, Perla de León, Pablo Delano, Máximo Colón, and Francisco Reyes II–had no intention of documenting algo como un nacimiento; if anything, they were trying to illuminate stubbornly resistant signs of life against a background of almost morbid decay.

The amazing thing about “Día,” a photographic exhibition recently shown in the arty Brooklyn neighborhood known as DUMBO, is how it records the birth of the Nuyorican. Yet the photographers–Frank Espada, Ricky Flores, David Gonzalez, Perla de León, Pablo Delano, Máximo Colón, and Francisco Reyes II–had no intention of documenting algo como un nacimiento; if anything, they were trying to illuminate stubbornly resistant signs of life against a background of almost morbid decay.

In these photographs, taken in the 1970s and ’80s, we see las caras linda de nuestra gente, algunos recién llegado de la isla, otros ya establecidos en esta nueva isla, Manhattan (y la ancla del archipelago, el Bronx). Although the Nuyorican is often thought of as having left behind la esencia de ser puertorriqueño, there are those caras, tocando el conjunto jíbaro, la bomba y la plena de San Antón, holding onto that flag like it was part of their own flesh.

In these photographs, taken in the 1970s and ’80s, we see las caras linda de nuestra gente, algunos recién llegado de la isla, otros ya establecidos en esta nueva isla, Manhattan (y la ancla del archipelago, el Bronx). Although the Nuyorican is often thought of as having left behind la esencia de ser puertorriqueño, there are those caras, tocando el conjunto jíbaro, la bomba y la plena de San Antón, holding onto that flag like it was part of their own flesh.

They are faces of people asked to live through recession after recession, the reduction of much of their home neighborhoods to piles of rubble and trash, to defend political prisoners and their own image from dismal stereotyping of sensationalist Hollywood films. They were the elders, who never quite learned English, young adults who let their hair run wild to their shoulders, helped to invent modern salsa, who did the freak and the bugaloo. And there were the children who hardly knew the calculated madness of the social experiment of urban depopulation they were forced to grow up in.

They are faces of people asked to live through recession after recession, the reduction of much of their home neighborhoods to piles of rubble and trash, to defend political prisoners and their own image from dismal stereotyping of sensationalist Hollywood films. They were the elders, who never quite learned English, young adults who let their hair run wild to their shoulders, helped to invent modern salsa, who did the freak and the bugaloo. And there were the children who hardly knew the calculated madness of the social experiment of urban depopulation they were forced to grow up in.

Delano’s work, the only series shot in color, is the most hopeful of the exhibition, signaling how the Lower East Side (later dubbed “Loisaida” by poets Bimbo Rivas and Jorge Brandón) became a successful corner of organized resistance by the Nuyorican community. Although plagued by the same problems as Boricuas in El Barrio uptown, the smaller buildings seemed to let more light into the frame. New York Times reporter David Gonzalez, enjoying a moment of exploration through photography as a recent college graduate in the early 1980s, focused on festive moments of pleasure as well as the carnivalesque procession of Nuyoricans on the streets during parades or street fairs.

Delano’s work, the only series shot in color, is the most hopeful of the exhibition, signaling how the Lower East Side (later dubbed “Loisaida” by poets Bimbo Rivas and Jorge Brandón) became a successful corner of organized resistance by the Nuyorican community. Although plagued by the same problems as Boricuas in El Barrio uptown, the smaller buildings seemed to let more light into the frame. New York Times reporter David Gonzalez, enjoying a moment of exploration through photography as a recent college graduate in the early 1980s, focused on festive moments of pleasure as well as the carnivalesque procession of Nuyoricans on the streets during parades or street fairs.

Joe Conzo, whose father was a close confidante of Tito Puente, had an insider’s view of the Nuyorican historical moment. He captures a street protest over the movie “Fort Apache: the Bronx,” which ironically starred Nuyorican poet Miguel Piñero, but was denounced by ex-Young Lord Richie Pérez because of its relentlessly negative depictions of Boricuas. He also freeze-frames an aging Héctor Lavoe, Machito, and Charlie Palmieri, and a beautiful piece by one of our most renowned street muralists, Manny Vega.

Frank Espada’s images are more stark, feeling more like Depression-era photography, with an emotional weight that captures the Nuyorican pre-history of the 1960s. Here we find the transplanted jíbaros, and the street corner preachers, and the strangely eerie sight of El Museo del Barrio’s Three King’s Day Parade trudging through the snow and under the iconic Park Avenue viaduct. One wonders what was on the other side? Espada seems to be soliciting guesses.

Frank Espada’s images are more stark, feeling more like Depression-era photography, with an emotional weight that captures the Nuyorican pre-history of the 1960s. Here we find the transplanted jíbaros, and the street corner preachers, and the strangely eerie sight of El Museo del Barrio’s Three King’s Day Parade trudging through the snow and under the iconic Park Avenue viaduct. One wonders what was on the other side? Espada seems to be soliciting guesses.

Among the most striking photos of the exhibition is the work of Máximo Colón, who created portraits of the living transformation we experienced in the ’70s. Here are photos of many who I seem to recognize hazily but can’t quite place, and some I do know, like the poet Sandra María Esteves, peeking through the hair of her infant child in 1975. There is a tremendous sense of nostalgia transmitted through that look of hers, as if she knew the moment wouldn’t last for long.

But of course, the moment lasted longer than we could have predicted. We no longer live in rubble, or at least it’s more of a metaphorical rubble. Las caras lindas persist, exploding in street colors, a rabble of bilingual energy and music, the template of style and substance for Latino (and black and white) New York. I salute these photographers for allowing us these half-lived, half-imagined memories.

mUCH ENJOY YOUR COMMENTARIES AND WEBSITE. IF YOU ARE EVER IN NORTHERN VERMONT OR NEED TO GET AWAY TO A HILLTOP SMALL FAMILY FARM, WE WOULD LIKE TO HAVE YOU VISIT AND STAY A WHILE. MANUEL Y MYRNA

Very deep educational and insparational info our history needs to be instilled in our youth the way white and black history had been for all these yrs